NOTE: At the end of this article is a podcast player that extends a conversation about the topic of Quality Circles. Enjoy the article.

Introduction to Quality Circles

In the ever-competitive world of business, organizations strive for continuous improvement in processes, products, and services. A crucial approach to achieving these goals is the implementation of Quality Circles, a concept that integrates teamwork, problem-solving, and employee engagement to enhance organizational performance. Originating in Japan, quality circles have become a cornerstone of Total Quality Management (TQM) practices worldwide.

In this dated Quality topic we explain the concept of Quality Circles in great detail. After reading this article, you will understand the basics of this powerful quality management tool. And while Quality Circles are somewhat of an older and dated concept, its general methodology is still very valid and can be used to expedite change at all levels of the organization.

A quality circle is a small group of employees who voluntarily come together to identify, analyze, and solve work-related problems. These groups are typically composed of 5 to 12 members from the same department or work area and are led by a facilitator. The primary aim of quality circles is to tap into the collective expertise of employees to improve productivity, quality, and efficiency within the workplace.

The concept was first introduced in Japan in the 1960s as part of the TQM movement. Inspired by the ideas of Dr. W. Edwards Deming and Dr. Joseph Juran, Japanese companies sought to involve workers at all levels in the quality improvement process. Quality circles gained global recognition after their success in companies like Toyota and Nissan, setting an example for organizations worldwide to follow. Today, quality circles are employed in various industries, from manufacturing to healthcare, showcasing their versatility and adaptability.

So What is Quality Circles?

Quality circles are small groups of employees who meet regularly to discuss workplace improvement, solve problems, and enhance productivity. This article will explore the various purposes that quality circles serve within organizations, highlighting their significance in fostering a culture of continuous improvement and employee engagement.

A Quality Circle is a participatory management technique that enlists the help of employees in solving problems related to their own jobs. Circles are formed of employees working together in an operation who meet at intervals to discuss problems of quality and to devise solutions for improvements. Quality circles have an autonomous character, are usually small, and are led by a supervisor or a senior worker. Employees who participate in quality circles usually receive training in formal problem-solving methods – such as brain-storming, pareto analysis, and cause-and-effect diagrams – and are then encouraged to apply these methods either to specific or general company problems. After completing an analysis, they often present their findings to management and then handle implementation of approved solutions.

The power of a Quality Circles comes from mutual trust between managers and employees, which leads to more mutual understanding. Generally, 5 to 12 members from the same work area make up the circle. Besides the tools mentioned above, the members might also receive training in more advanced tools such as deeper problem solving topics, statistical quality control, and group management tools. Quality circles generally recommend solutions for quality and productivity problems which management then may implement. A facilitator, usually a specially trained member of management, helps train circle members and ensures that things run smoothly. Typical objectives of Quality Control programs include quality improvement, productivity enhancement, and employee involvement. Circles generally meet four hours a month on company time.

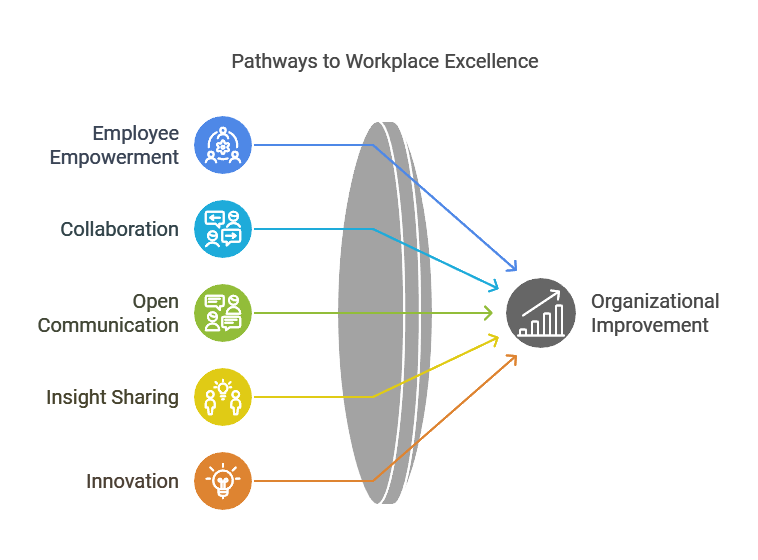

Quality circles aim to empower employees by involving them in decision-making processes related to their work environment. By encouraging collaboration and open communication, these circles help identify issues and develop solutions that can lead to improved efficiency and effectiveness. Additionally, quality circles serve as a platform for employees to share their insights and experiences, which can lead to innovative ideas and practices that benefit the organization as a whole.

Whenever possible, workers implement the solutions themselves in order to improve the performance of the organization, which increases employee engagement. The true purpose of these circles is to develop workers into effective problem solvers, with the side benefit of achieving efficiency and quality gains in the process.

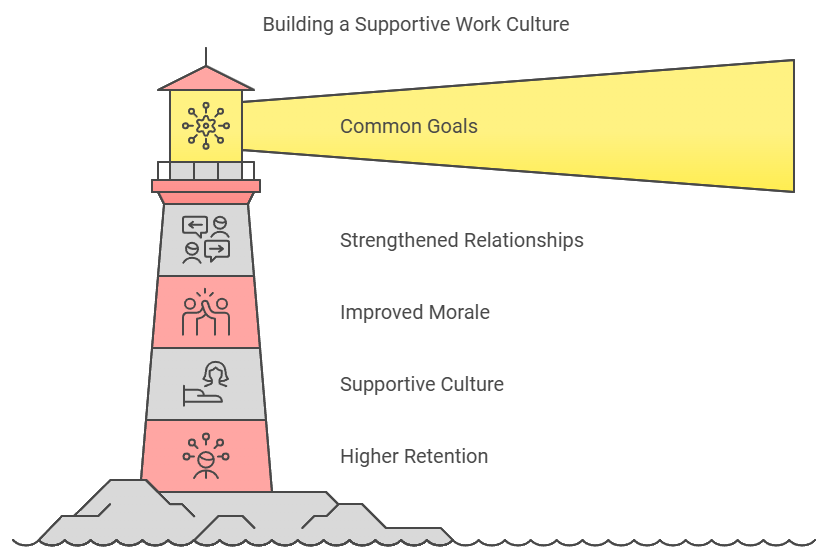

Another key purpose of quality circles is to enhance team dynamics and build a sense of community among employees. By working together towards common goals, team members can strengthen their relationships, improve morale, and foster a supportive work culture. This collaborative approach not only boosts employee satisfaction but also contributes to higher retention rates and reduced turnover.

Quality circles also play a crucial role in promoting a culture of continuous improvement. By regularly assessing processes and outcomes, organizations can identify areas for enhancement and implement necessary changes. This proactive approach helps organizations stay competitive and responsive to market demands, ultimately leading to better overall performance.

One more side benefit to Quality Circles is to build towards a good relationship with employees, so they will show more interest and devotion in the work they do. This will result in increased quality, productivity and cost reduction.

History of Quality Circles

Original Quality Circle Path

Quality circles were originally associated with Japanese management and manufacturing techniques. The introduction of quality circles in Japan in the postwar years was inspired by the lectures of W. Edwards Deming (1900—1993), a statistician for the U.S. government. Deming based his proposals on the experience of U.S. firms operating under wartime industrial standards. Noting that American management had typically given line managers and engineers about 85 percent of the responsibility for quality control and line workers only about 15 percent, Deming argued that these shares should be reversed. He suggested redesigning production processes to account more fully for quality control, and continuously educating all employees in a firm—from the top down—in quality control techniques and statistical control technologies. Quality circles were the means by which this continuous education was to take place for production workers.

Deming predicted that if Japanese firms adopted the system of quality controls he advocated, nations around the world would be imposing import quotas on Japanese products within five years. His prediction was vindicated. Deming’s ideas became very influential in Japan, and he received several prestigious awards for his contributions to the Japanese economy.

The principles of Deming’s quality circles simply moved quality control to an earlier position in the production process. Rather than relying upon post-production inspections to catch errors and defects, quality circles attempted to prevent defects from occurring in the first place. As an added bonus, machine downtime and scrap materials that formerly occurred due to product defects were minimized. Deming’s idea that improving quality could increase productivity led to the development in Japan of the Total Quality Control (TQC) concept, in which quality and productivity are viewed as two sides of a coin. TQC also required that a manufacturer’s suppliers make use of quality circles.

Quality circles in Japan were part of a system of relatively cooperative labor-management relations, involving company unions and lifetime employment guarantees for many full-time permanent employees. Consistent with this decentralized, enterprise-oriented system, quality circles provided a means by which production workers were encouraged to participate in company matters and by which management could benefit from production workers’ intimate knowledge of the production process. In 1980 alone, changes resulting from employee suggestions resulted in savings of $10 billion for Japanese firms and bonuses of $4 billion for Japanese employees.

Active American interest in Japanese quality control began in the early 1970s, when the U.S. aerospace manufacturer Lockheed organized a tour of Japanese industrial plants. This trip marked a turning point in the previously established pattern, in which Japanese managers had made educational tours of industrial plants in the United States. Thereafter quality circles spread rapidly here; by 1980, more than one-half of firms in the Fortune 500 had implemented or were planning to implement quality circles. To be sure, these were not installed uniformly everywhere but introduced for experimental purposes and later selectively expanded—and also terminated.

In the early 1990s, the U.S. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) made several important rulings regarding the legality of certain forms of quality circles. These rulings were based on the 1935 Wagner Act, which prohibited company unions and management-dominated labor organizations. One NLRB ruling found quality programs unlawful that were established by the firm, that featured agendas dominated by the firm, and addressed the conditions of employment within the firm. Another ruling held that a company’s labor-management committees were in effect labor organizations used to bypass negotiations with a labor union. As a result of these rulings, a number of employer representatives expressed their concern that quality circles, as well as other kinds of labor-management cooperation programs, would be hindered. However, the NLRB stated that these rulings were not general indictments against quality circles and labor-management cooperation programs, but were aimed specifically at the practices of the companies in question.

Second Quality Circle Path

Quality circles were then improved by Kaoru Ishikawa in the early 1960’s, and the approach was circulated through the Japanese industry by JUSE. It was most popular during the 1980s, but continues to exist in the form of Kaizen groups and similar worker participation schemes. Details of the approach are described in Ishikawa’s 1988 book, “What is Total Quality Control?: The Japanese Way” and the books, “Fundamentals of QC Circles” and “How to operate QC Circle Activities” published by the QC Circle Headquarters, part of the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE).

Nippon Wireless and Telegraph Company was the first company in Japan to apply Quality Circles in 1962. By the end of that year, there were 36 companies registered with JUSE who were using this approach. By 1978, the movement had grown to an estimated 1 million teams, involving over 10 million Japanese workers.

Quality circles first appeared in Japan. It was Japanese professor Kaoru Ishikawa who first used the term Quality Circles and made it accessible in his 1985 manual ‘What is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way’. The underlying idea was to systematically include employees from all levels in the organization-wide production of quality.

Many businesses in Europe and the United states also adopted working with Quality Circles, including Hewlett-Packard and Coleman. Quality circles have been implemented even in educational sectors in India, and QCFI (Quality Circle Forum of India) is promoting such activities. However this was not successful in the United States, as the idea was not properly understood and implementation turned into a fault-finding exercise – although some circles do still exist. Don Dewar together with Wayne Ryker and Jeff Beardsley established quality circles in 1972 at the Lockheed Space Missile factory in California.

Quality Circle Consigned

In the mid-2000s, Quality Circles were almost universally consigned to the dustbin of management techniques. James Zimmerman and Jamie Weiss, writing in Quality, summed the matter up as follows: “Quality and productivity initiatives have come and gone during the past few decades. The list of ‘already rans’ includes quality circles, statistical process control, total quality management, Baldrige protocol diagnostics, enterprise wide resource planning and lean manufacturing. Most have been sound in theory but inconsistent in implementation, not always delivering on their promises over the long run.”

Nilewide Marketing Review said the same thing in similar words: “Management fads should be the curse of the business world—as inevitably as night follows day, the next fad follows the last. Nothing more typifies the disastrous nature of this following so-called excellence than the example of quality circles. They rose to faddish heights in the late 80s presenting the so-called secret of Japanese companies and how American companies such as Lockheed used them to their advantage. Amid all the new consultancies and management articles, everyone ignored the fact Lockheed had abandoned them in 1978 and less than 12% of the original companies still used them.”

Harvey Robbins and Michael Finley, writing in their book, Why The New Teams Don’t Work, put it most bluntly: “Now, we know what happened to quality circles nationwide—they failed, because they had no power and no one listened to them.” Robbins and Finley cite the case of Honeywell which formed 625 quality circles but then, within 18 months, had abandoned all but 5 of them.

Japanese industry obviously embraced and applied quality circles (the idea of an American thinker) and QC has contributed to Japanese current dominance in many sectors, notably in automobiles. If QC became a fad in the U.S. and failed to deliver, implementation was certainly one important reason – as Zimmerman and Weiss pointed out. U.S. adapters of QC may have seen the practice as a silver bullet and did not bother shooting straight. The reason why a succession of other no doubt sensible management techniques have also, seemingly, failed to get traction may be due to a tendency by modern management to embrace mechanical recipes for success without bothering to understand and to internalize them fully and to absorb their spirit.

Any experienced manager, contemplating the rules shown above and the typical management environments in which he or she works or has worked in the past will be able to discern quite readily why QC has not taken a firm hold in the U.S. environment. As for the small business owner, he or she may actually be in a very good position to try this approach if it feels natural. An obviously important element of success, confirmed by Ron Basu and J. Nevan Wright, is that QC must be practiced in an environment of trust and empowerment.

Interest in Quality Circles

The interest of U.S. manufacturers in quality circles was sparked by dramatic improvements in the quality and economic competitiveness of Japanese goods in the post-World War II years. The emphasis of Japanese quality circles was on preventing defects from arising in the first place rather than through culling during post-production inspection. Japanese quality circles also attempted to minimize the scrap and downtime that resulted from part and product defects. In the United States, the quality circle movement evolved to encompass the broader goals of cost reduction, productivity improvement, employee involvement, and problem-solving activities.

The quality circle movement, along with total quality control, while embraced in a major way in the 1980s, has largely disappeared or undergone significant transformations.

But like all business and quality methods and techniques, quality circles are simply that – just a method or technique. Companies do not know what will work for their environment and therefore should not to quality circles by the wayside. Quality circles are simply a method that a company can potentially use, if they believe the method might fight their culture and environment. Do not treat it like a fad or a fly by night process. If the program seems as though it would work for your organization, simply take it on a test run and evaluate the possibility.

Quality Circle Implementation

Quality Circles Methodology

Below are the Quality Circle methodologies that are key to the implementation and use of Quality Circles. Each of the below methodologies should be a focused item by the team as a whole.

Improve Communication – Effective communication is the foundation of successful Quality Circles. It encourages open dialogue between team members, ensuring that everyone understands the objectives, shares ideas freely, and addresses issues collaboratively. By fostering transparency, Quality Circles help reduce misunderstandings, promote knowledge sharing, and build a culture of trust within the organization.

Create Problem-Solving Capabilities – Quality Circles enhance the problem-solving skills of employees by involving them in identifying, analyzing, and resolving workplace issues. This hands-on approach empowers employees to think critically, explore creative solutions, and implement strategies that lead to continuous improvement.

Create a Problem Hindrance Attitude – Developing a proactive attitude toward addressing problems is a key outcome of Quality Circles. Employees learn to view challenges not as obstacles but as opportunities for growth and improvement. This shift in mindset fosters resilience and a solution-focused approach.

Develop Leaders and Employee Relationships – Quality Circles provide a platform for employees to take initiative, demonstrate leadership, and work collaboratively with peers and supervisors. By engaging in group activities, team members build strong interpersonal relationships and mutual respect, enhancing overall workplace harmony.

Build Positive Attitude in Workforce – Participating in Quality Circles instills a sense of accomplishment and belonging among employees. This positive reinforcement boosts morale, encourages a forward-thinking outlook, and cultivates an environment where employees feel valued and motivated to contribute.

Develop Knowledge and Skill – Continuous learning is a core element of Quality Circles. Through training sessions, problem-solving exercises, and collaborative discussions, employees gain new technical and interpersonal skills that benefit both individual career growth and organizational performance.

Develop Safety Awareness – Safety is a critical aspect of workplace operations. Quality Circles focus on identifying potential hazards, analyzing their causes, and implementing preventive measures. By promoting a culture of safety awareness, organizations reduce accidents and ensure a secure working environment.

Reducing Mistakes – Quality Circles aim to minimize errors by improving processes, streamlining workflows, and ensuring that employees are well-informed about their tasks. This results in higher productivity, fewer reworks, and greater overall efficiency.

Teamwork – Collaboration is at the heart of Quality Circles. Team members work together to achieve common goals, leveraging diverse perspectives and strengths. This teamwork fosters a sense of unity and shared responsibility, which enhances both individual and group performance.

Increase Work Motivation – When employees are involved in decision-making and see the impact of their contributions, their motivation naturally increases. Quality Circles empower employees by giving them a voice and an active role in improving their work environment, leading to higher job satisfaction and commitment.

Core Principles of Quality Circles

Quality circles operate based on several fundamental principles:

Voluntary Participation – Employees join quality circles on their own accord, ensuring genuine interest and commitment. This voluntary nature fosters enthusiasm and a sense of ownership.

Bottom-Up Approach – Problem-solving and decision-making are driven by employees closest to the issues, fostering practical and actionable solutions tailored to ground realities.

Team Collaboration – Members collaborate to identify problems, brainstorm solutions, and implement improvements, leveraging diverse perspectives and fostering mutual respect.

Continuous Improvement – Quality circles aim for incremental, ongoing enhancements rather than one-time fixes. The focus on sustainability ensures long-term benefits.

Empowerment – Employees are empowered to take ownership of their work environment and contribute to organizational success, leading to increased motivation and job satisfaction.

The Process of Quality Circles

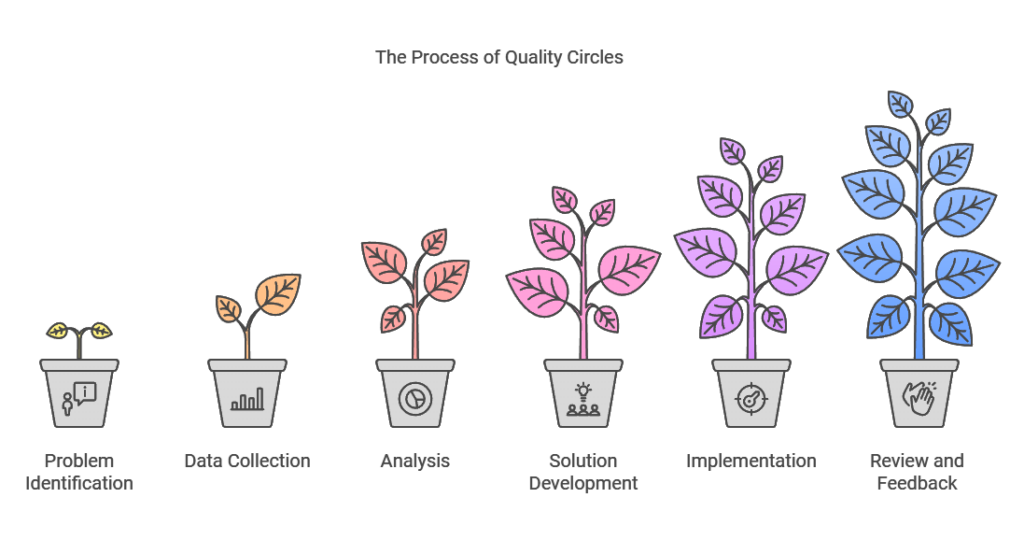

Quality circles follow a structured process to address workplace challenges:

Problem Identification – Members identify specific issues affecting their work or department. These could range from inefficiencies in processes to quality defects in products, creating a prioritized list of concerns.

Data Collection – The group gathers relevant data to understand the problem thoroughly. This involves quantitative and qualitative analysis to ensure accuracy.

Analysis – Using tools like cause-and-effect diagrams, Pareto charts, and flowcharts, the circle analyzes the problem to pinpoint root causes. The aim is to address the underlying issue rather than symptoms.

Solution Development – Members brainstorm potential solutions and evaluate their feasibility. Innovative ideas are encouraged, ensuring diverse approaches to problem-solving.

Implementation – Once a solution is agreed upon, the team develops an action plan for implementation, detailing timelines, responsibilities, and required resources.

Review and Feedback – After implementing the solution, the circle evaluates its effectiveness and identifies any further improvements. This step ensures accountability and ongoing learning.

Benefits of Quality Circles in a Business Environment

The adoption of quality circles offers numerous advantages to organizations, employees, and customers. Here are some of the key benefits:

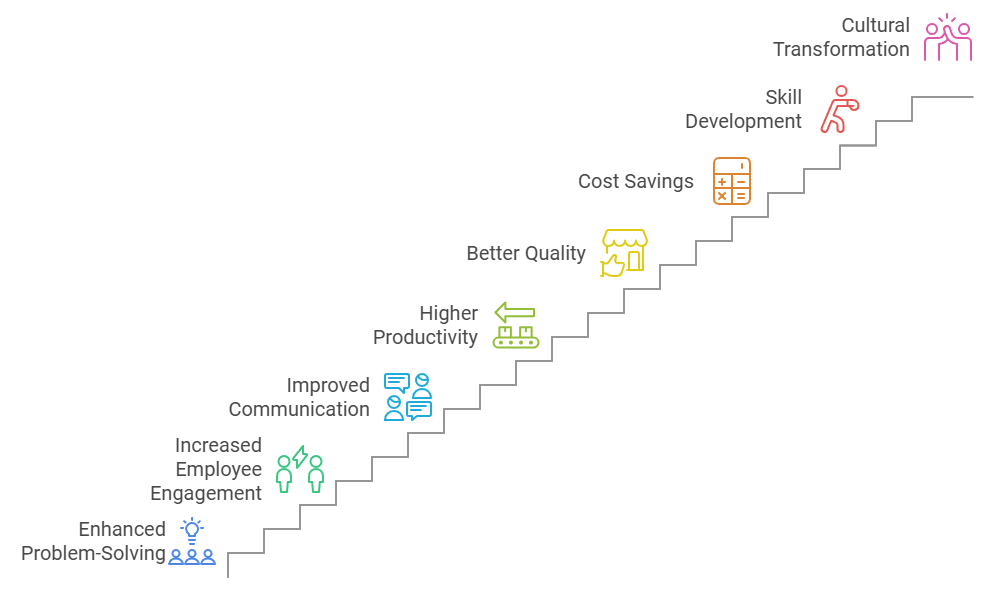

Enhanced Problem-Solving – Quality circles leverage the collective knowledge and experience of employees, leading to innovative and effective solutions. Employees closest to operational issues provide practical insights that management might overlook.

Increased Employee Engagement – Participation in quality circles boosts morale and job satisfaction by giving employees a voice in decision-making. Engaged employees are more likely to be loyal and motivated.

Improved Communication – The collaborative nature of quality circles fosters open communication among team members and across departments. This improved dialogue minimizes misunderstandings and promotes alignment.

Higher Productivity – By addressing inefficiencies and streamlining processes, quality circles contribute to increased productivity, allowing organizations to optimize resources.

Better Quality – Continuous improvements in processes and products result in higher quality outcomes, enhancing customer satisfaction and brand reputation.

Cost Savings – Identifying and eliminating waste or defects reduces operational costs. These savings can be reinvested in growth initiatives.

Skill Development – Employees develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and leadership skills through their involvement in quality circles, creating a more capable workforce.

Cultural Transformation – Over time, quality circles can transform organizational culture, making it more collaborative, innovative, and responsive to change.

Implementing Quality Circles: Key Steps

For organizations looking to establish quality circles, the following steps can ensure successful implementation:

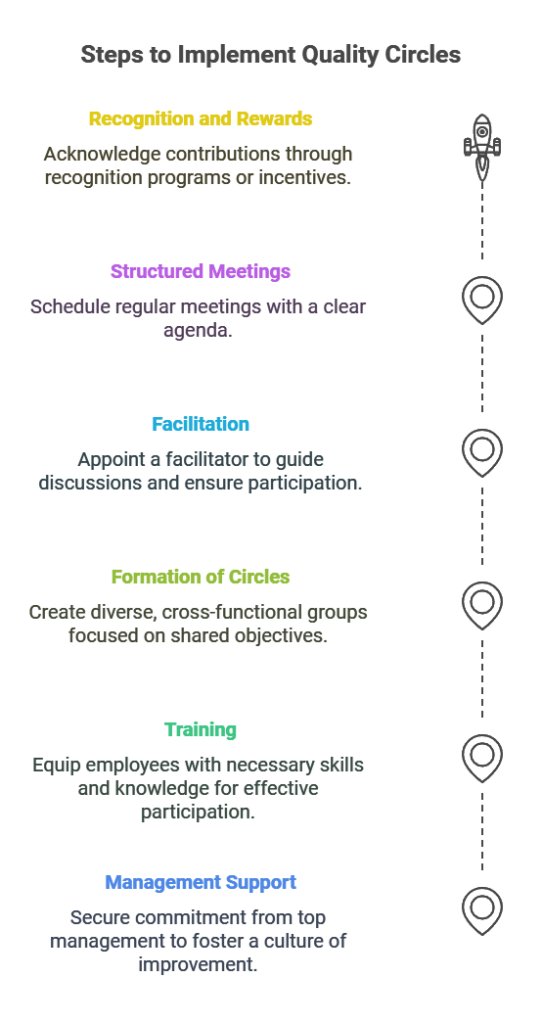

Management Support – Secure commitment from top management to provide the necessary resources and foster a culture of continuous improvement. Visible support from leaders reinforces the importance of quality circles.

Training – Equip employees with the skills and knowledge required to participate effectively in quality circles, including problem-solving techniques, data analysis methods, and team dynamics. Training fosters confidence and competence.

Formation of Circles – Create small, cross-functional groups based on shared work areas or objectives. Diversity within circles can enrich discussions and solutions.

Facilitation – Appoint a facilitator to guide discussions, ensure participation, and maintain focus. Facilitators play a critical role in steering circles towards productive outcomes.

Structured Meetings – Schedule regular meetings with a clear agenda to discuss problems and solutions. Consistency ensures sustained progress.

Recognition and Rewards – Acknowledge the contributions of quality circles through recognition programs or incentives to sustain motivation. Public appreciation can inspire wider participation.

Tools and Techniques Used in Quality Circles

Quality circles rely on a variety of tools and techniques to analyze problems and develop solutions. Some commonly used tools include:

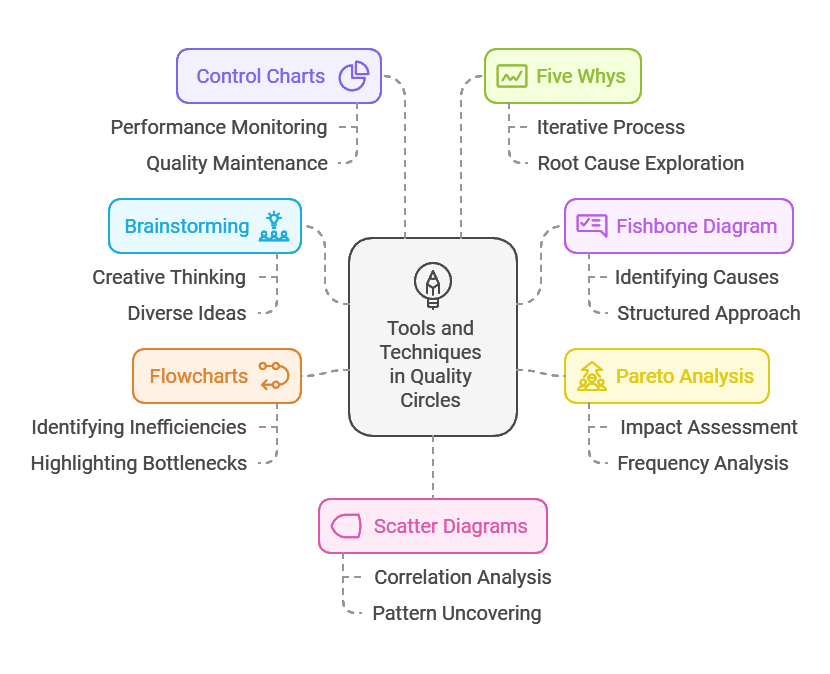

Brainstorming – Encourages creative thinking and generates diverse ideas. Members feel free to share without fear of judgment.

Fishbone Diagram (Cause-and-Effect Diagram) – Identifies potential causes of a problem, providing a structured approach to root cause analysis.

Pareto Analysis – Prioritizes issues based on their impact or frequency, ensuring focus on high-value areas.

Flowcharts – Maps out processes to identify inefficiencies, highlighting bottlenecks or redundancies.

Control Charts – Monitors process performance over time, enabling timely interventions to maintain quality standards.

Five Whys – Explores the root cause of a problem by repeatedly asking “why.” This iterative approach ensures depth in analysis.

Scatter Diagrams – Analyzes correlations between variables, uncovering patterns that might influence outcomes.

Requirements for Success

The problems of adaptation, which have caused Quality Circles to be abandoned, are made plain by a look at the conditions two experts think are necessary for the success of Quality Circles. Ron Basu and J. Nevan Wright, in their book Quality Beyond Six Sigma (another quality management technique) specified seven conditions for successful implementation of Quality Circles. These are summarized below:

- Quality circles must be staffed entirely by volunteers.

- Each participant should be representative of a different functional activity.

- The problem to be addressed by the QC should be chosen by the circle, not by management, and the choice honored even if it does not visibly lead to a management goal.

- Management must be supportive of the circle and fund it appropriately even when requests are trivial and the expenditure is difficult to envision as helping toward real solutions.

- Circle members must receive appropriate training in problem solving.

- The circle must choose its own leader from within its own members.

- Management should appoint a manager as the mentor of the team, charged with helping members of the circle achieve their objectives; but this person must not manage the QC.

“Quality circles have been tried in the USA and Europe, often with poor results,” Basu and Wright say. “From our combined first-hand experience of quality circles in Australasia, the UK and Europe, South America, Africa, Asia and India, we believe that Quality Circles will work if [these] rules are applied.”

Case Studies Information

In a structures-fabrication and assembly plant in the south-eastern US, some quality circles (QCs) were established by the management (management-initiated); whereas others were formed based on requests of employees (self-initiated). Based on 47 QCs over a three-year period, research showed that management-initiated QCs have fewer members, solve more work-related QC problems, and solve their problems much faster than self-initiated QCS. However, the effect of QC initiation (management- vs. self-initiated) on problem-solving performance disappears after controlling QC size. A high attendance of QC meetings is related to lower number of projects completed and slow speed of performance in management-initiated QCS. QCs with high upper-management support (high attendance of QC meetings) solve significantly more problems than those without. Active QCs had lower rate of problem-solving failure, higher attendance rate at QC meetings, and higher net savings of QC projects than inactive QCs. QC membership tends to decrease over the three-year period. Larger QCs have a better chance of survival than smaller QCs. A significant drop in QC membership is a precursor of QC failure. The sudden decline in QC membership represents the final and irreversible stage of the QC’s demise. Attributions of quality circles’ problem-solving failure vary across participants of QCs: Management, supporting staff, and QC members.

Toyota Motor Corporation: Toyota’s use of quality circles is a key component of its renowned Toyota Production System (TPS). Employees at all levels participate in identifying inefficiencies and suggesting improvements. For instance, a quality circle at a Toyota assembly plant proposed a change in the layout of tools, reducing production time by 15%. This initiative not only enhanced efficiency but also boosted employee morale.

IBM: In the 1980s, IBM implemented quality circles to address declining productivity and quality. Employees identified process bottlenecks and proposed automation solutions, resulting in a 20% increase in efficiency within two years. The program also improved cross-departmental collaboration, fostering a unified approach to problem-solving.

Tata Steel: In India, Tata Steel has been a pioneer in adopting quality circles. The company’s employees have solved numerous operational challenges, such as reducing energy consumption in blast furnaces, leading to significant cost savings and environmental benefits. Tata Steel’s emphasis on quality circles has positioned it as a leader in sustainability and innovation.

General Electric (GE): GE utilized quality circles as part of its Six Sigma initiative to streamline operations. Employees identified redundancies in supply chain management, reducing delivery times by 25%. This success demonstrated the scalability of quality circle practices.

The Life and Death of Quality Circles

QC Circles were designed to be a way for people to actively take pride in their work by having a voice in making it better. But Circles often became a management tool focused on cutting costs (and jobs), and on finding fault. Deming excerpted a speech from Dr. Akira Ishikawa (who became president of Texas Instruments in Japan) about why Circles worked in Japan but not in the US. “In the U.S., a QC-Circle is normally organized as a formal staff organization, whereas QC-Circle in Japan is an informal group of workers.”

The second contrast is the selection of the theme for a meeting and the way in which the meeting is guided. In the U.S., the selection of a theme or project and how to proceed on it are proposed by a manager. In contrast, in Japan, the things are decided by the initiative of the member-workers.

The third feature is the difference in hours for a meeting. A meeting in the U.S. is held within working hours. A meeting in Japan may be held during working hours, during the lunch period, or after working hours.

In the U.S., monetary reward for a suggestion goes to the individual. In Japan, the benefit is distributed to all employees. Recognition of group achievement supersedes monetary benefit to the individual.

These aren’t just procedural or technical differences. They’re fundamental. The way that Circles are implemented can determine whether or not employees tap into their innate needs for control, competence, and connection.

“One Japanese plant manager who turned an unproductive U.S. factory into a profitable venture in less than three months told me: ‘It is simple. You treat American workers as human beings with ordinary needs and values. They react like human beings.’

Once the superficial, adversarial relationship between managers and workers is eliminated, they are more likely to pull together during difficult times and to defend their common interest in the firm’s health. Without a cultural revolution in management, quality control circles will not produce the desired effects in America.”

Challenges to Quality Circles

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their benefits, quality circles can face challenges, including:

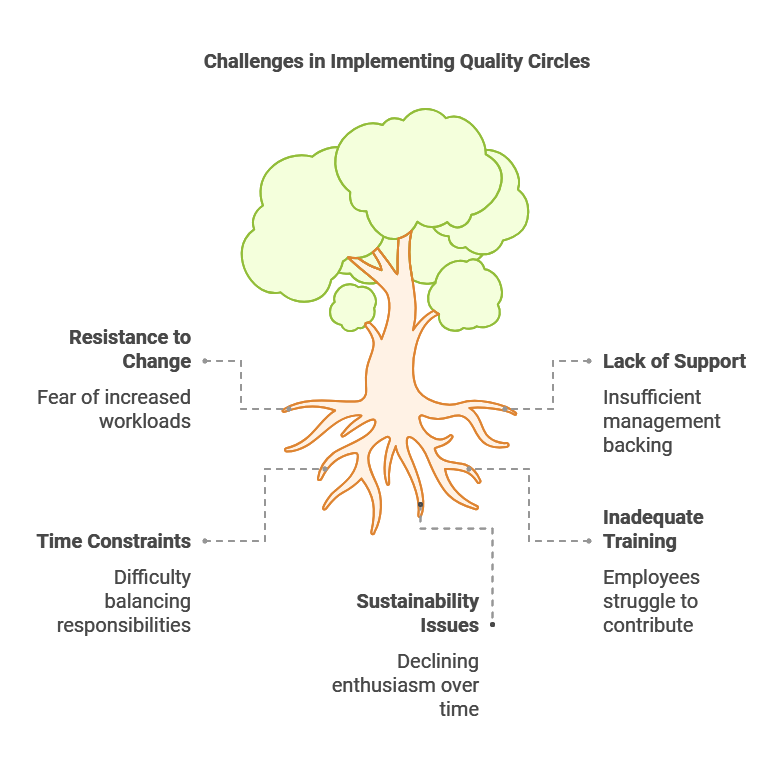

Resistance to Change – Employees or managers may be reluctant to adopt new practices, fearing increased workloads or disruption.

Lack of Support – Insufficient backing from management can hinder the effectiveness of quality circles, limiting resources or recognition.

Time Constraints – Balancing circle activities with regular job responsibilities can be challenging, especially in high-pressure environments.

Inadequate Training – Without proper training, employees may struggle to contribute meaningfully, reducing the circle’s effectiveness.

Sustainability Issues – Maintaining enthusiasm and participation over time can be difficult, leading to stagnation.

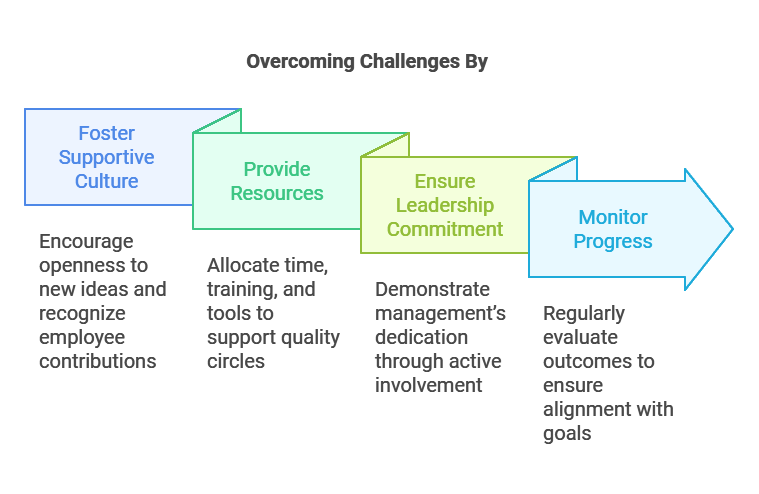

Overcoming Challenges

Organizations can address these challenges by:

Fostering a Supportive Culture – Encourage openness to new ideas and recognize employee contributions, creating an environment where quality circles can thrive.

Providing Resources – Allocate time, training, and tools to support quality circles. Investing in infrastructure demonstrates commitment.

Ensuring Leadership Commitment – Demonstrate management’s dedication to quality improvement initiatives through active involvement and communication.

Monitoring Progress – Regularly evaluate the outcomes of quality circles to ensure alignment with organizational goals. Use feedback to refine practices.

In Summary

Composition

Employees show more loyalty and devotion to their organization when they are open to collaboratively define and solve problems concerning quality or performance. This is easiest when it concerns smaller teams. It is a requirement that they voluntarily participate in the Quality Circle and meet regularly. The concept of the Quality Circle is based on mutual respect, in which there is no place for assumptions and suspicion. The small group is best led by a manager. It is important that the participants in the Quality Circle have the correct knowledge and are trained beforehand by the so-called facilitators; experts in the area of personnel and employment relationships.

Subjects

Quality Circles offer employees the opportunity to use all their experience, knowledge and creativity to bring improvement into their activities. They are able to convert challenging problems into opportunities with the solution they offer themselves. Employees are generally free to select subjects in the Quality Circles. Some typical subjects that are extremely suitable for discussion in circles are improvements concerning health and safety at work, improvement concerning the workplace and concerning production processes and the product design.

Conditions

To truly do Quality Circles justice, it is important to meet several conditions. In the first place, the mood needs to be relaxed. People need to feel comfortable and be free to share their own opinion. Every member of the Quality Circle also needs to get their turn. This is the only way for employees to feel involved and be interested, which will motivate them to contribute. There is also a need to determine a clear goal, so everyone knows what is expected of them. People need to be open to each other’s point of view and listen to all opinions. If an action emerges, clear agreements must be made that are accepted by all employees.

Implementation

To contribute to a Quality Circle, it is recommended to first create a quality control group within the organization, which is represented by managers that know production, quality control and process planning. This control group’s task is to follow the Quality Circle. A facilitator will also need to be appointed, as well as a chair who is capable of getting all conversations in the circle to run smoothly. Apart from the responsibility to lead a Quality Circle, they need to give each employee the opportunity to participate in the discussion and motivate them to come up with creative ideas. The chair is in close contact with the facilitator. The facilitator functions as a link between top management, the Quality Circle and its members and middle management. They coordinate training courses, so all employees know the ins and outs of working in a Quality Circle. Another task of the facilitator is to create support and get support from everyone involved with the quality circle.

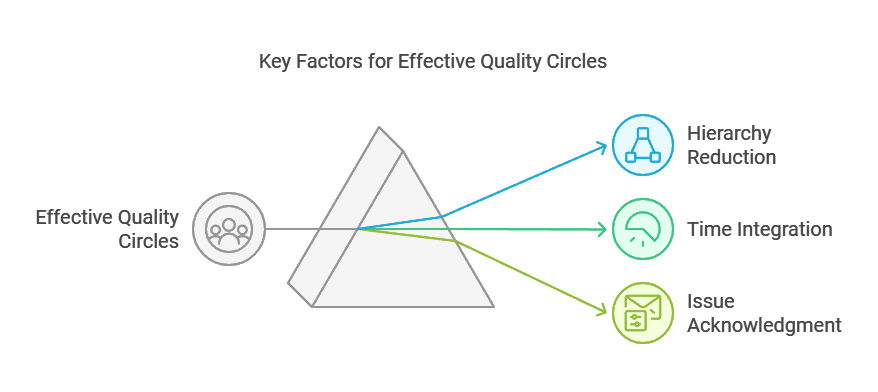

Focus Areas

Quality Circles can only function when there is an interest in letting go of hierarchy. Where managers set themselves up as leaders, employees will not be motivated to participate in the circle. Employees can also not be expected to participate in the meetings of the Quality Circles outside office hours or without payment. An organization would do well to integrate this into work time. Finally, problems that are raised by employees must not be allowed to be ignored. It is precisely the aim to improve the quality in all levels of the organization.

Last Note

Is the concept of a Quality Circle applicable in your professional environment? Do you recognize the practical explanation or do you have more suggestions? What are your success factors for good participation management? Can Quality Circles still be a valid form for change within an organization?

The Future of Quality Circles

As businesses adapt to technological advancements and evolving market demands, the concept of quality circles continues to evolve. The integration of digital tools, such as data analytics, artificial intelligence, and collaborative software, enhances the effectiveness of quality circles by providing real-time insights and facilitating remote collaboration. Moreover, the emphasis on sustainability and social responsibility has broadened the scope of quality circles to include environmental and ethical considerations, ensuring relevance in a rapidly changing world.

Final Conclusion

Quality circles represent a powerful tool for organizations seeking to foster collaboration, innovation, and continuous improvement. By empowering employees to take an active role in problem-solving, businesses can achieve significant gains in quality, productivity, and employee satisfaction. Despite challenges, the enduring relevance of quality circles underscores their value as a cornerstone of organizational success in a dynamic business environment. As industries evolve, quality circles will continue to play a pivotal role in shaping the future of work, driving excellence, and creating a culture of shared responsibility and innovation.

Podcast

Check out this podcast about the topic of Quality Circles.